My father-in-law served during WWII as a navigator on a B-24 bomber in the Army Air Corp. His service was cut short when his plane went down in Nadzab, New Guinea. Most of the men on the airplane died in the crash. Every year on the anniversary of the crash, the co-pilot would call and they would catch up. I think at the request of this other man, my father-in-law recorded the events as he remembered them. Here are his words. Alert, the account is long. In memory of him and in attempt to preserve the account, I’m retyping and posting his type-written recollection.

Nadzab, New Guinea

May 21, 1944

“This is my best recollection of what happened in New Guinea on May 21, 1944. I believe my recollection to be good even forty-five years later, but since I sometimes think that this could never have happened to me, some minor details may be inaccurate. I have never until this year discussed these events with anyone else who would have any knowledge of what happened.

We were a B-24 bomber crew on a mission to bomb the island of Biak held by the Japanese just north of the western part of New Guinea. The distance was over 700 miles one way, so it would be a ten or twelve hour flight. The plane was a new one–never having been flown in combat before that day.

We were leading a flight and it is my hazy recollection that we, therefore, had an extra enlisted man on the crew. I believe he was a radioman.

The flight to the target was uneventful, but when we got near the south coast of Biak, we encountered some flak. Although I do not remember any flak close to us at that time we lost an engine. I am not certain but I believe it was the number two engine.

The pilot, Tom Janusz, or the co-pilot, Ed Kubitz, feathered the bad engine and we continued to lead the flight and drop our bombs on the Japanese headquarters area, which was our target. We then turned to return to our base at Nadzab still leading our flight.

On the way back the pilot tried the dead engine and it apparently worked well. We continued on all four engines until we got in sight of our field at Nadzab. We were either in our final approach to land or very close to it when two or three of the engines–I am not certain how many or which ones–began to cut out and in.

It is my understanding that we were unable to turn onto the runway because of the terrain and the admonition of never turning into your bad engine–or in this case, perhaps bad engines. As a result the pilot decided to attempt to keep the plane aloft until we could get to an emergency landing strip further up the Markam River or gain enough altitude to bail out.

The pilot and co-pilot were in their seats. As navigator, I was seated at my desk directly behind the pilot. The bombadier, Charles Gill, was standing to my right directly under the top gun turret and the crew chief, an enlisted man, was also on the flight deck.

It is strange that I cannot remember the names of most of the enlisted men. But I can remember their faces and physical descriptions vividly–well enough to describe them for an artist’s drawing.

We were very low having lost our altitude in preparing to land. The co-pilot ordered the enlisted crew to bail out, but in my judgment, we did not have enough altitude and I ordered them to the rear bombay bulkhead, supposedly the safest crash position. To this day I wonder whether I lost five lives or saved two. All the officers remained on the flight deck.

I attempted to put on my parachute harness and snap on my chute, but my harness was twisted and I could not snap it on. I remember very vividly thinking that if I took off the harness to straighten it out we might momentarily gain enough altitude to bail out. I was afraid that then everybody else would leave the plane and leave me all alone struggling with my chute. I remember that I was not so much afraid of crashing as I was that I might be left alone on the plane. I mustered all the strength I could and forced the chute on the harness in a twisted fashion. I still wonder if it would have opened properly if I had had the chance to bail out.

Even though the co-pilot obviously thought the crew could bail out safely, he made no attempt to bail out himself but continued to help the pilot try to keep the plane up long enough to get to the emergency strip.

I have often thought with amazement about how well the entire crew behaved in this emergency situation. I must admit that I had often thought about this before these events and I felt that some of them would not perform well. There was no panic. Everyone was under complete control.

The plane would pull up a few feet and then settle and this continued for a short period. Then suddenly we hit the trees. We must have stalled out and hit nose down for I do not remember cutting any path through the trees.

When the plane hit there was one large thump and then I remember a period of absolute silence. It seemed like several seconds elapsed and then I saw the pilot float straight up in the air and through the roof. Again, several seconds seemed to elapse and then the co-pilot appeared to float out to the right through the side of the plane. Again several seconds seemed to elapse and I felt myself floating very slowly up in the air and through the roof. I have no recollection at all of the bombadier who was standing inches away to my right.

How we could break through the roof or sides of the plane I cannot imagine. I recollect that later I saw only a cut on the bridge of the nose of the pilot. The co-pilot’s face or head were unmarked and I had cuts on my scalp and one under my chin.

I felt myself flying through the air and I landed in some large bushes or saplings in the jungle. I believe I landed feet first and then I hit on my back where I believe I had a jungle pack which may have saved me from worse injury. I have always felt that I was conscious throughout this perieod although because of the slow motion I remember I must have been close to unconscious.

I was very uncomfortable because I was lying on the bent bushes and saplings, but I felt no pain. My lower right leg was pointed out at almost a right angle and looked grotesque. I straightened it out with my hands so that it would look more normal. I was told later by the doctors that in doing so I had probably saved my leg. But they said that in doing so I had also taken the chance of cutting all the blood vessels and bleeding to death.

There was no debris from the plane visible to me and I could not see any other crewmen. I called out and one voice answered me and pleaded with me to help him. I could not make him understand that I could not move to help him and he kept pleading to me for help. Eventually he quit and I later assumed that he was one of the men who died at the scene.

I remember looking at my watch either just before the crash or while I was lying there just after the crash. It was 4:45 p.m. After a short while some natives came to the scene and approached me. They appeared friendly but could not understand me.

I got my parachute off the harness and threw it toward the natives. They took it and ran off into the jungle. I often think that they knew what they had and were delighted to get all that nylon for dresses for their girlfriends or wives.

My sensation as I lay there waiting for help was one of extreme happiness. I guess I was just lucky to be alive and I knew that I would be going home.

It was quite a while before help arrived. My recollection is that it was about six hours. I vaguely remember that it was still daylight, so it could not have been that long. They came up the bed of the Markam River in trucks to get to us. We stayed overnight at the scene of the crash and were were evacuated the next morning by a C-47 which landed in a clearing near the scene.

This was the first time I remember seeing any other members of our crew. I remember vividly that the co-pilot tried to keep them from putting him on the C-47. Apparently he wanted no parts of an airplane so soon after this experience.

We were flown to the 3rd Field Hospital. I believe it was near Nadzab. I was put in an ambulance with the bombadier. My right leg was all busted up with the bones protruding though the flesh so I was in a lot of pain during the ride to the hospital. I believe the bombadier, who appeared not to be hurt, had walked onto the C-47. During the ride to the hospital he was lying on a stretcher, but he kept getting up on one elbow to steady my stretcher and kept telling the ambulance driver to take it easy because I was having a lot of pain from the rough ride.

At the hospital the pilot, co-pilot and I were together, but the bombadier was not with us. I thought this was probably because he was not hurt. A few days later we were told that he had died of internal injuries.

The doctor took one look at me and said, “Son, the armistice for you was signed on May 21, 1944. You’re going home.” That was one of the happiest moments of my life. I was ready.

I had severe lacerations of my scalp and under my chin and an obviously broken right leg. Other than bruises and contusions, this appeared to be all. Howver, when they tried to put me up on crutches in a few days, I could not stand on my left leg. They discovered that I had fractured the top of the left fibula and the left peroneal nerve had been severed. Because of this I was to spend eighteen months in army hospitals–mostly New England General at Atlantic City, New Jersey.

The pilot had only a slight cut on the bridge of his nose and after a few days of observation he went back to duty with the 90th Bomb Group. He visited the hospital a couple of times, but after that I never saw him or heard anything of him again.

The co-pilot to the best of my knowledge at that time had only a broken back. I remember that he was in a lot of pain. I was told that most of the pain was from kidney stones that had formed as a result of the large doses of sulfa drugs that we had all been taking to prevent infection. Penicillin was not yet available.

After the crash I do not remember seeing any of the enlisted men. I was told that only two survived. This seems strange because at the crash they were at the rear bombay bulkhead, supposedly the safest position, while the officers were on the flight deck, supposedly the most dangerous position.

In January or February, I met Ed Kubitz, the co-pilot at a convalescence hospital in Miami, Florida. It is strange, but I do not remember us talking much about the crash.

This is the first time I have ever written anything about the events of May 21, 1944, although I have spoken of it often. I have tried to be candid and give the facts as I recall them and I believe my recollection is excellent. I have not had the advantage of checking my recollection with anyone else who was involved. Any inaccuracies in this account are unintentional.”

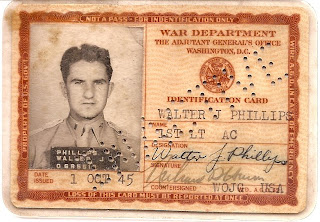

1st Lt. Walter J. Phillips

0-685513

So, there you have it. Just one example of the type of courage and sacrifice demonstrated by thousands of service people. They do deserve recognition, respect and our deep appreciation. My father-in-law went on to attend the University of Michigan and Harvard Law School thanks to the GI Bill. He was a great story teller and no-nonsense type of guy. Tough as nails and extremely smart, constructive and productive. He lived a good, long life. At 80 years old, he was cutting firewood with a chain saw just days before he died of pneumonia.

In Memory